After leaving school in the summer of 1952, I saw a job advertised in the Sunderland Echo for a clerk at a firm of Chartered Accountants. I applied by letter and got an interview, it was quite daunting; my first attempt at joining the grown-up workforce. My mother came with me, I was terrified, I felt like I was being thrown to the wolves. I was all of four foot eight and a half inches tall and there I was out in the big bad world having to fend for myself. I had the interview and heard nothing for a couple of weeks, and then a letter arrived informing me that I was the successful applicant. I had managed to secure a job in one of the top firms in Sunderland.

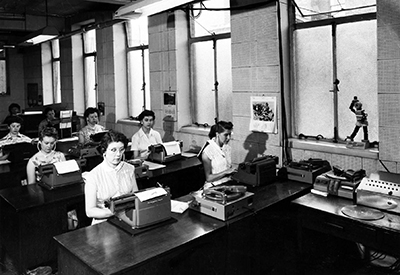

On my first morning, I arrived nice and early at the offices of T.C. Squance & Sons. I introduced myself to a chap behind a large counter; he turned out to be the head office boy. I was to become his junior, his name was Cyril. I was then taken upstairs to meet the chief clerk and be briefed on my duties and what would be expected of me. The firm consisted of five partners and about thirty journeyman accountants. There was also a group of ladies, who did all the typing in the typing pool and a comptometer operator, who used to check all the figures on a comptometer. Some of the journeymen were only trainees and I was to join the firm at the bottom of the pile but my future looked bright.

I began work under the guidance of Cyril, the duties were quite simple: general run-around for the journeymen and the partners, and manning the telephone exchange when Margaret, the telephonist, was at lunch. My first and last duty of the day was to handle the mail. I had to go to the General Post Office to pick up the company mail, which was held in a great big leather satchel, then deliver it back to the office for 9 a.m. At the end of the day, I had to take the satchel back to the General Post Office with the outgoing mail.

People were very cost-conscious in those days and if a letter was addressed to a firm within a three-quarter-mile radius of the office, it was delivered by hand, and again this was one of my duties. I soon got to know the business district of Sunderland quite well. I must have walked miles and miles; we delivered twice a day.

The general office had to do an audit of its books every morning, this comprised of checking the day-book, the petty cash box and the stamp book, making sure that the cash and the stamp book tallied to the last ha’penny stamp. You would think this was an easy task. Well it was not. At least once a week, the books did not balance, this was to be frowned on when you think about the size and prestige of the firm. So, as the junior, I was taught how to ‘cook the books’. Usually the stamps would be out by the odd ha’penny or tuppence-ha’penny, which was the cost of posting a letter. The day-book was a great big, leather-bound ledger about two-and-a-half inches thick, in which was entered a record of all the outgoing mail by name, address, and whether it was hand-delivered or posted. The price of the stamps was annotated in a column alongside. Well, if I was tuppence-ha’penny out in the daily reckoning, I would look for a name on the outer edge of the delivery route and change its status to posted, hence the books balanced and if I was only a ha’penny out, I would just add it to a letter and say it was overweight. Same result and the books balanced beautifully every day.

After about three months, Cyril was promoted to the upstairs’ offices and became part of the journeyman team, training to become an accountant “on the shop floor” you might say. I, myself, was promoted to the grand status of head office boy. Wow! What responsibility for a young lad of fifteen. A new office boy started on the Monday and I was in charge, I taught him all I knew about the job and gave him instructions about picking up the mail and letter deliveries. We were paid the princely sum of twenty-five shillings for a forty-four-hour week.

I had only been head office boy for about a month when my career was cut short. Another couple of weeks and I would have been promoted and moved to the upstairs’ offices to begin my true accountancy career. Alas, it was not to be. I had sent the new office boy to the Post Office to purchase some stamps. I had given him a list and a pound note from the petty cash box, this was a lot of money in those days. Well, to my misfortune he lost the money, I had to go to the chief clerk, cap in hand, to explain the situation. Immediately I was paraded in front of Mr. Squance, the head of the firm, to explain. His reaction was to call for an immediate audit of the general office accounts. Unfortunately for me, the accounts for that day were found to be out of balance, by tuppence ha’penny, the price of a stamp.

Loyalty was also a trait in those days, so I could not tell him how the books had been fiddled for centuries. I kept mum; he probably knew anyway. We’d had no time to do the daily fiddle, he was shocked and made the decision that his secretary would have the task of checking the day-book for the next week. She was an old battle-axe as I rightly remember. The next day they were okay, but sure enough on the third day they were again askew; she would not have a bar of fixing it in the way that had gone on for years. So, as the head office boy, I was given two weeks’ notice of dismissal and that was that. Just imagine, here we were, one of the top accountancy firms in Sunderland and we could not keep our daily accounts in order, my goodness!

I was heartbroken, but that was how the system worked. How could I get a reference now? However, what I did was to deliver the company mail myself, instead of having the junior do it. On my travels between customers I thought I would look out for a job. I was lucky, as one of our clients was looking for an office boy and I said I needed a job because I didn’t like working in the accountancy field. He offered me the job and I was to start in a couple of weeks after I’d served my notice; he never did find out I’d been sacked.

Even though Squance’s was giving me the boot, I still felt this sense of duty towards them. I was working late one evening, while serving out my notice. It was a very large general office. I was over in one corner in the shadows, doing a bit of filing ready for my hand-over to my successor, when I heard someone bounding down the stairs then bursting through the double doors into another corner, where there was a very large safe. He pulled out a bunch of keys, opened the safe, took out two stamps, put them on a couple of envelopes and duly locked up the safe before proceeding to leave the office. He hadn’t seen me in the corner and I yelled out, “What are you doing?” He replied, “Posting the company mail after working late”. I then asked if he was going to update the day-book, he asked me why, and I retorted, “Because the books won’t balance in the morning and you are the reason why I’m being dismissed”. He was all-apologetic and said he would square it with the chief clerk on the Monday. I asked how long he’d been doing this, and he casually said, “For years”. No wonder the books were out of balance so often. He was one of the senior accountants as well. On the Monday morning, I was called into the chief clerk’s office, where I was told I would be re-instated. Unfortunately, I am quite a stubborn little bugger and refused reinstatement. Thus ended my career in accountancy.